AD5508

The Illustrator- John Cuneo

Introduction

Through this essay, I shall be exploring and discussing the practise and processes of American illustrator John Cuneo (b. 1957)[1]. I will be investigating any cultural, historical or technological changes that may have affected his work or how he works. I will also be comparing Cuneo’s work with that of his historical parallels, such as T.S. Sullivant and A.B. Frost. To further my investigation, I will contextualise Cuneo’s work with contemporaneous practising illustrators to understand his place in today’s current industry and refer to writings of commentators such as John Berger to truly understand Cuneo’s illustrations. I shall finish the essay by evaluating Cuneo’s practise in relation to his impact in the creative industry.

Cuneo’s Process and Practise

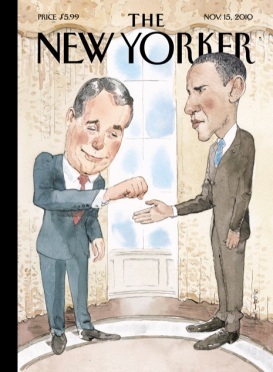

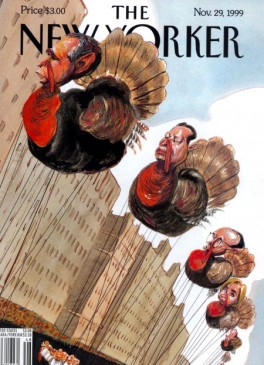

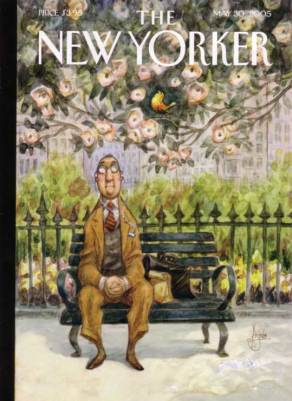

John Cuneo is a renowned editorial illustrator in the USA. He has featured in publications such as, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Esquire and Time Magazine amongst others[2]. Only over the past 20 years has Cuneo been focusing on editorial work. He previously produced illustrations for advertising purposes, however he realised his work was more apt to editorial illustration. He also states that in the future he would love to diversify in other areas such as children’s books.[3]

Cuneo has had no formal means of art training[4]. He explains that he spent two semesters at the Colorado Institute for Art and learnt about the colour wheel[5]. He considers his real education to be that of socialising with other illustrators and how that has affected his practise, he’ll watch Steve Brodner draw caricatures on napkins or study Barry Blitt working on a sketch for The New Yorker or sit in Peter de Sève’s studio while he sketches for the Ice Age films. From his friends, he states he learns about how to conduct himself as a professional and “how to live a life without being consumed by drawing pictures.”[6] However, in regards to how Cuneo develops his artistic skills, he says it’s a case of ‘trial and error’. His ink and watercolour drawings are a result of decades of practising different techniques.[7]

One could express that Cuneo’s lack of training has enabled him the freedom to draw figures in an original way with no set rules. His long-limbed and grotesquely-shaped figures are a significant staple to his style and how his work is perceived by viewers.

“Over the years I’ve tried to free myself from some of the academic “rules ” of making a picture. Partly to keep myself entertained with the process. I have a pretty specific, “literal” cartoon (or whatever) style. It’s based on some fundamental drawing precepts which demand that the figures look “real” enough to work in the picture. It’s a kind of tight-assed way to make funny drawings, so to break up that fundamentally grounded aspect, I try and allow myself a lot of freedom with scale, gravity and asymmetry.”- John Cuneo [8]

“I‘m easily influenced, and a lifetime of insecurity has resulted in some embarrassing stylistic shifts. I have to be careful not to wallow in the works of my heroes too long, or I’ll tend to get off track with what I’m really after with my own thing.” – John Cuneo [9]

The above quote refers to Cuneo separating himself from current illustrator’s work otherwise he will be consumed by the thought that he isn’t good enough or that he should change his style of work[10]. However, Cuneo does express certain historical artists that have influenced his work. A. B. Frost being just one of them.[11]

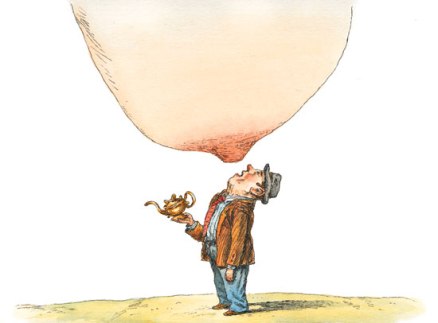

Fig 1. A.B. Frost- ‘He tries it on his wife’

(no date stated)

One illustration of a few drawings from a small narrative about a man wanting to try out hypnotism. The next illustration in the set is the man on the floor, holding his head.

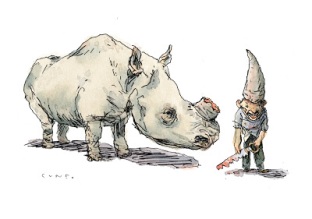

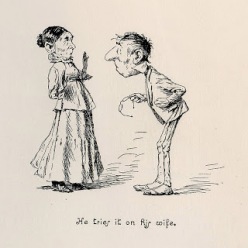

Fig 2. John Cuneo- ‘Thank you, but I’m already shit-faced’.

(no date stated)

A piece of personal work by Cuneo.

The similarities between Frost’s and Cuneo’s work are abundant. [Above] In Fig 1. and Fig 2. both artists stress certain features of the figures to create playful and characterful cartoons. Moreover, the figures don’t need to be standing in a specified location, the figure’s actions give the illustration the context needed by the viewer to appreciate what is happening. A.B. Frost (b.1851)[12] was also an editorial illustrator and had a rich and prevalent career in the now known ‘Golden Age of American Illustration’, so Frost is a key figure in American art history, there is much for Cuneo to take inspiration from, perhaps even the simple use of pen and ink. To the further that point, a second American illustrator from the early 20th century that Cuneo states as an influence is T.S. Sullivant [13] (b.1854)[14]. Sullivant, much the same as Frost was an American editorial cartoonist who mainly used pen and ink for his illustrations. It’s clear that Cuneo uses the same techniques that traditional cartoonists used, except Cuneo has developed his work into an edgy and off-beat expression of himself. The subjects he chooses to portray are always very current and are there to reinforce a point he’s trying to convey to viewers. For example, Fig. 4 certainly emulates this, not just the grim realisation that the Rhinoceros’ horn is being worn by a man, but the grimace on the man’s face being the more alarming of the two. Cuneo has adapted innocent, mildly humorous pen and ink drawings that would be typical of the early 20th century to harder and grittier versions of events as he views them, using A.B. Frost and T.S. Sullivant’s work as initial inspiration.

Direct Contemporaries

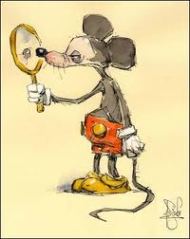

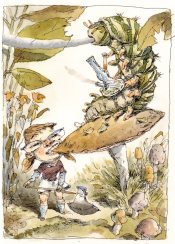

Both artists showing a new take on classic children’s characters.

As mentioned earlier in the essay, John Cuneo socialises with many of the illustrators in the editorial circuit today, especially those in New York City. Many of those who I consider to be his direct contemporaries are the illustrators that illustrate for The New Yorker, as Cuneo does. These illustrators include Barry Blitt, Steve Brodner and Peter de Sève.

“The editorial illustration world’s a pretty small community, I suppose. And it is very competitive as far as getting work, but the people I’ve mentioned here are all very supportive friends — maybe it’s because they don’t think of me as a threat?”

Cuneo explains that the art director of The New Yorker, Francoise Mouly, has a shortlist of artists that he contacts with new projects[15]. This ‘New Yorker list’ is a very select group of artists that Cuneo just happens to be great friends with. So much so, they threw him a fiftieth birthday party.[16]

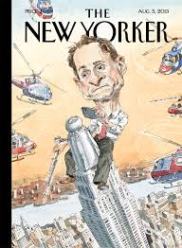

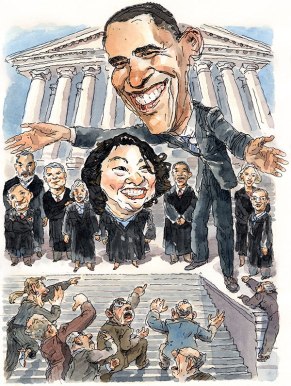

As Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10 show [above], Cuneo is part of a caricature and cartoon revolution in American publication. He speaks in interviews of how he learns from his peers and often talks in admiration of Barry Blitt’s drawings[17]. Cuneo also explains that the ‘style’ of his work now has only been established for the last ten to fifteen years[18], so his current practise put into context with his direct contemporaries means he is always learning and adapting his drawings, especially the subject matter, be it political or social satire.

“…Steve Brodner and others have been around this block before (Barry Blitt built the damn block) and have provided great, informative posts.” – John Cuneo commentating on Fig. 10 [above] and how he tried to make the drawing his without it being generic or too similar to his peers’ work. [19]

Changes that affected Cuneo’s practise

A frequent change that affects Cuneo’s work is politics and current affairs. Much of Cuneo’s work is centered around American politics which, as we all know, is ever-changing. Cuneo’s caricature work is aimed almost exclusively at the political world and because it is ever-changing, Cuneo is never short of subject matter to turn into satirical commentaries on the way his nation is governed.

Referring back to Fig.10- ‘Anthony Weiner’

–“Mr. Wiener may wind up being the Mayor of New York City, but at this point, it’s hard to deny that he is also a walking dick joke. For a cartoonist, he is an embarrassment of riches (or a richness of embarrassments). As a subject of satire, the man is a target-rich environment.”- John Cuneo [20]

Caricatures of well-known congressmen and other political figures are the height of popularity for editorial publications and John Cuneo has settled into a group of New York based illustrators/cartoonists that will relish in the forever-changing world of politics.

Cuneo has also been affected by technological changes. He states in an interview aimed at young, budding illustrators that he is from a generation who aren’t that ‘comfortable’ with technology, and who aren’t about to start now this far into their careers. Cuneo explains that his nephew is studying concept art for video games and he naively thought “Well, how else can you make a living drawing pictures if you’re not making stuff for The New Yorker or Esquire?”. He continues by saying, that he is almost exclusively a magazine illustrator, and it’s tough for anyone with no technological background to find work in the ever-shrinking newspaper market, “…unless you’re one of those guys who’s got a syndicated comic strip…”. [21]

Another change is the fluctuating need for illustrations. An issue that affects any illustrator. John Cuneo has been a freelance illustrator for thirty years and it’s never been steady. He describes his success as ‘lucky’, he has had stretches where there has been no work and he has been worried about money amongst other things, but equally times where there has been more than enough work. He expresses that this industry is not for the ‘meek’.[22]

The final change in John Cuneo’s life as an illustrator, is culturally he has expanded his knowledge of the world and of what illustration is. He is extremely open about having no formal art training and explains that as he was growing up there was no ‘fine art’ around his house and that his parents were not ‘culturally sophisticated’. The only illustrations he knew were in the few books that were in his house or the cartoons in the newspaper, and he would take advantage of the abundance of books in the library[23]. However, now, Cuneo sees his illustrative influences to be Harry Rountree’s classic illustrations or even new, contemporary illustrators such as Marcel Dzama’s clean and hauntingly whimsical drawings. Cuneo even confesses to looking at Rembrandt’s etchings almost everyday[24]. This confirms that his knowledge has expanded and that lack of art training doesn’t mean there is a lack of available inspiration in the world. Furthermore, his close friendships with leading New York/American illustrators would have also dramatically affected his practise. As stated earlier in the essay, his friends don’t teach him how to draw, he observes them and they provide the knowledge they’ve learnt at art school about how to conduct yourself on a project and how to be a professional. This aspect of Cuneo’s life and practise as an illustrator, I think, has been the most substantial change to allow his overwhelming success as an editorial illustrator.

John Berger’s ‘Ways of Seeing’ applied to Cuneo’s practise

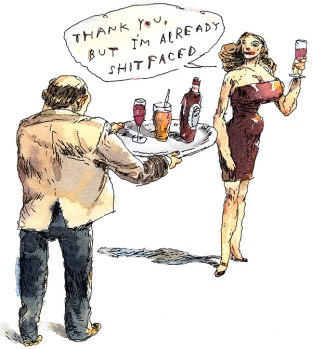

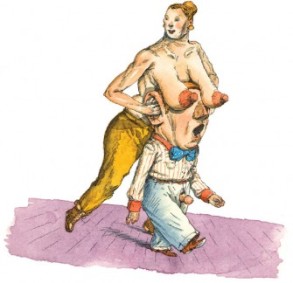

One area of Cuneo’s practise I’ve yet to discuss, is his published book of pieces and sketches named ‘nEuROTIC’[25]. The book, published in 2007, is filled with cartoons of a some what shocking, occasionally violent and frequently sexual disposition[26]. I am applying John Berger’s ‘Ways of Seeing’ to this area of Cuneo’s work because I am eager to explore whether the philosophy still prevails when this particular body of work was never supposed to be seen and why Cuneo has opted for this particular subject matter.

Fig. 12- Untitled -John Cuneo. This image features on the front of the book. This piece won a Gold Medal from the Society of Illustrators and also features in the American Illustration annual. Cuneo expresses that he doesn’t have a favourite piece in the book but he was ‘thrilled’ by the response to this one.

“The painter’s way of seeing is reconstituted by the marks he makes on the canvas or paper. Yet, although every image embodies a way of seeing, our own perception or appreciation of an image depends also upon our own way of seeing.”- John Berger [27]

Many writers and commentators tell of artists producing the work they do because it is an expression of themselves. But every artist must be conscious of who the viewer may be. A deliberately provocative artist, for example Damien Hirst, produces his outlandish art to provoke a reaction from the viewers. Is every artist subconsciously bound by the ties of, how Berger puts it, “…assumptions about art. Assumptions concerning: Beauty, truth, genius, civilization, form, status, taste etc…” ? [28]

However, John Cuneo explains these drawings as practise pieces at a time when he was dissatisfied with the kind of work he was producing[29]. He filled a few sketchbooks of finished pieces and then left them to gather dust in a cupboard. It wasn’t until a few close friends of his saw them that they came out and he was encouraged to show them to a larger scale of people[30]. I think these drawings and illustrations are more raw, and we are seeing the true artist here. There is no subconscious appeal for an audience, so these pieces are as close as we are getting to the real John Cuneo. Any assumptions we make as the viewers are not about the piece itself, we, now, are nothing to do with the piece, instead, we make our assumptions on John Cuneo and his character and personality, and appreciate the piece for what it is in relation to him.

Fig. 14-John Cuneo- Untitled

Cuneo warns viewers of the content in the book, by explaining that the work is sexually orientated and inappropriate for children. In one case, on his website, he expresses that his personal work may be seen as vulgar or ‘lacking merit’. [31]

“Every time we look at a photograph, we are aware, however slightly, of the photographer selecting that sight from an infinity of other sights.”- John Berger [32]

Cuneo describes the themes he may have been thinking of whilst drawing some of these illustrations were the ‘intersection of lust’, ‘ambivalence’ and the ‘attraction/repulsion reflex towards the ways of the flesh’. However he still remains firm by the fact that he doesn’t look for a deeper meaning to his work, he is a humorous illustrator and that is what he strives to convey as his visual language.[33]

So, Cuneo’s choice of erotic subjects for these illustrations are his own personal preference and what he finds amusing they were not intended to be seen by the masses. Berger writes about pieces being presented as a work of art and how people look upon that ‘work of art’ are based purely on assumption of what we think a work of art should be[34]. But these pieces were never presented so on what basis should we judge whether these illustrations are (as reviewers have put it) “a full colour 96-page cry for help…”. Personally, I believe that this series of illustrations in Cuneo’s book ‘nEuROTIC’ are some of his strongest pieces of work. They are the most imaginative and they have an infinite amount of depth to them. Even John Berger writes, “the more imaginative the work, the more profoundly it allows us to share the artist’s experience of the visible.”[35]

Conclusion

In conclusion to my investigation of John Cuneo’s practise, I have learnt that Cuneo’s has been deeply affected by the support of his good friends who are also his illustrative competition. His editorial practise has been shaped around what he has learnt from them more so then the very little experience he has had at art school. His lack of formal training has made his work original and it emulates that of traditional early 20th century, American cartoonists.

Changes to his practise have been by politics, always providing new material for him to create a satirical piece, technological changes preventing him from being anything other than a magazine illustrator and cultural changes, educating himself as to what art is and what it means.

Finally, what makes John Cuneo an important, significant and a relevant illustrator today is his innate ability to choose worth-while subjects to illustrate and do it so organically they can’t help but be engrained in our memory.

References

1. John Cuneo biography- Google search

2. Official John Cuneo website

3. James, (2011) EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

4. Caleb. M, “Life of a Magazine Illustrator”, article

5. Caleb. M, “Life of a Magazine Illustrator” , article

6. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

7. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

8. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

9. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

10. James, (2011) EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

11. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

12. A.B. Frost biography- Google search

13. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

14. T.S. Sullivant biography- Google search

15. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

16. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

17. James, (2011) EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

18. James, (2011) EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

19. Cuneo, (2013), Blog post

20. Cuneo, (2013), Blog post

21. Caleb. M, “Life of a Magazine Illustrator” , article

22. Caleb. M, “Life of a Magazine Illustrator” , article

23. Caleb. M, “Life of a Magazine Illustrator” , article

24. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

25. Official John Cuneo website

26. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

27. Berger, (1972) “Ways of Seeing” Publication

28. Berger, (1972) “Ways of Seeing” Publication

29. James, (2011) EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

30. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

31. Official John Cuneo website

32. Berger, (1972) “Ways of Seeing” Publication

33. Spurgeon, (2007), “A Short Interview With John Cuneo” article

34. Berger, (1972) “Ways of Seeing” Publication

35. Berger, (1972) “Ways of Seeing” Publication

Bibliography

Berger, J. Ways of Seeing, 1972. Published by the British Broadcasting Corporation, London. Also published by Penguin Books, Penguin Group, London.

Caleb.M. “Life of a Magazine Illustrator”

http://www.goodlifeyouthjournal.com/Good_Life_Winter.pdf

Cuneo, John. 2013, ‘cover’ Blog post.

http://drawger.com/johncuneo/?article_id=14399

James, Thomas. 2011, EFII Podcast Episode 75- John Cuneo

http://illustrationage.com/2011/03/23/efii-podcast-episode-75-john-cuneo

John Cuneo Official Website

Spurgeon, Tom. 2007, “A Short Interview With John Cuneo”.

http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/resources/interviews/7874/